- Home

- Marvin Tokayer

The Fugu Plan Page 15

The Fugu Plan Read online

Page 15

There was never any question but that they would accept as many refugees as could possibly reach Japan. Dealing with transient refugees on a large scale, however, required more organization than the community possessed. The result of the July meeting was a total mobilization: Committees were put together to cope with immigration procedures, temporary housing, local travel, onward travel, visa problems, and so on. A request for funds was cabled to the Joint Distribution Committee in New York. The reply read simply: SAVE JEWS MONEY NO OBJECT. The name "Kobe Jewcom," from the cable address, was adopted. In the space of a long evening, twenty-five families in Kobe had been brought out of their comfortable routines and into an international spotlight.

Officially, the first several hundred East European Jews to pass through Kobe - unlike those who came later courtesy of Consul Sugihara and the Curacao visa - were not "refugees" in the strictest sense of the word. Each had a valid destination visa in hand for somewhere in North or South America. Theoretically, as far as these first transients were concerned, Kobe should have been only a way station en route from the landing at Tsuruga to a reembarkation at Yokohama. If any help had been required, the Yokohama Jewish community might normally have been expected to handle the last-minute problems. But the Yokohama community consisted of only eight families and these were primarily German Jews. Historically, there is something of a split in the European Jewish world: the Russian and East European Jews tend to have an affinity for each other; and the Western European Jews (German and Austrian) work more easily together. Consequently, when the Western European Jews began leaving the Continent as early as 1934, they turned to the predominantly German community in Yokohama. The East European Jews (predominantly from Poland) reached out to the Russian Jews of Kobe.

The Jews of Yokohama were as generous with their time and energy and kindness as those in Kobe. The situation that they had had to respond to, however, was quite different. The earlier German and Austrian refugees had been permitted to take with them only a little in the way of personal belongings, but they all had legitimate passports and visas. And, thanks to the efficiency of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society in Berlin, and because there was usually enough time to make arrangements ahead, most of those refugees had precise travel schedules and some knowledge of the lands and conditions through which they would be traveling.

In the case of the East European Jewish refugees, however, after the emotional upheaval of having been driven from their homes and having to seek uncertain shelter in a land of which they knew nothing, and after grueling physical hardships which culminated in a long trek across Siberia, they were in no state to continue on to anywhere immediately. Exhausted, undernourished often to the point of illness, and economically destitute, they were physically and emotionally incapable of coping immediately with the intricacies of normal Japanese immigration and travel procedures and the last minute snags that often arose in working out final visa and travel arrangements. Thus, it quickly became apparent to Kobe Jewcom that its most serious problem was the lack of time allowed the refugees in Japan.

The standard Japanese transit visa was good for only twenty-one days. Even a simple problem, if it had to be solved by sending a letter across the ocean to the United States, would take longer than three weeks to straighten out. And the problems of the East European refugees were rarely simple. The strict time limit naturally made the refugees anxious and made Kobe Jewcom's problems all the harder. On one or two occasions during June and July, 1940, transit visas were extended on an emergency basis. But what was needed was a general, across-the-board extension that would relieve some of the pressure from both the refugees and Kobe Jewcom.

With this problem preying on his mind, Ponve heard with great interest the news that Dr. Kotsuji had returned to Japan and was now living in the city of Kamakura, not far from Tokyo. Kotsuji, the Hebrew-speaking Christian minister who had been the senior adviser on Jewish policy for the South Manchurian Railway, was in an excellent position to help Jewcom. Though he had no official standing in the Japanese government, he did have the ear of one of the top men in the cabinet - his former supervisor at the railway, now foreign minister, Yosuke Matsuoka. On behalf of Kobe Jewcom, Ponve went up to Kamakura, and by the time he left, Kotsuji had agreed to do whatever he could about the visa problem.

Kotsuji spent days plodding through the normal lower echelons of the bureaucracy, arguing that, in the name of humanity, the soon-lapsing transit visas should be extended. Having no success whatsoever, Kotsuji realized he had to play his trump card. He would see Matsuoka in Tokyo.

Kotsuji arranged to meet the foreign minister in his office at the Gaimusho. Once there, he outlined the problem: the transit visas of many of the refugees would soon expire. If they could not be extended or renewed, these Jews, having no destination before them, would have to return where they had come from. And that meant sure death. Kotsuji knew well enough that Matsuoka's experiences, both in the United States where he had studied and in Manchukuo, had convinced him that far from being the "scum of the earth," Jews were people who tended to have skills and connections that could be highly beneficial to Japan. In fact, Kotsuji knew that while he was in Manchukuo, Matsuoka had been working on a plan to have Jews actually settle in the region, a plan he occasionally referred to as the fugu plan - though what its precise details were and what had come of it, Kotsuji had no idea.

No matter how Matsuoka might feel personally about Jews, however, he was surrounded by some strong political realities. In the autumn of 1940, the military was solidifying its hold on the Japanese government. The Tripartite Pact, which Matsuoka himself had signed in September, had pledged military unity between Japan and Germany. Already, the Nazis were expressing their displeasure at the presence of so many Jews in Japan. Clearly, Matsuoka was in a difficult situation and nervous about even discussing such a controversial subject. Eventually, the minister suggested they take a walk.

The two men left the eight-story, dark brick Gaimusho and walked in silence the brief distance to the ancient wooden Cherry Blossom Gate which led into the Imperial Palace grounds. Turning right, they strolled along beside the peaceful palace moat.

"Quite clearly, the international situation and our military alliances make it absolutely impossible for the government to make any official statement or take any official action favorable to the Jews," Matsuoka said as they walked unheard beneath the bare branches of the willows that lined the moat. "Moreover, there is no precedent for extending the transit visas of foreigners in Japan. If we were to do so, particularly on a mass scale and specifically for Jews, the repercussions from Germany would be overwhelming."

That much, Kotsuji thought, he could have told me in his office. He waited for the minister to continue.

"You are well aware that I have expressed, in the past, a belief that Japan might benefit greatly, at some time in the future, if we could in some way manage to help Jews now. I still hold that view. But it is my personal view and must not be repeated. You would not, of course, repeat it," he said, looking straight at Kotsuji. The latter quickly shook his head.

The two men spent nearly an hour discussing this problem as they had discussed similar ones during the nine months they had worked together in Manchukuo. Over lunch, far from the restaurants frequented by Gaimusho officials, Matsuoka arrived at a solution.

"Kobe is not Tokyo. If the local authorities were to extend the visas, acting on their own, without informing the Tokyo authorities of what they were doing, we would probably never even know about it. Can you lead them to understand that?"

Yes, Kotsuji thought he could.

"Good. Now you must understand our official position with no doubt: If Kobe ever asks the government's opinion concerning visa extensions of any sort, we will insist on a strict application of the law. But as long as everything is achieved on the local level. . . . Even better," he continued, refining the idea as he went along, "Jews themselves are efficient. Let them handle the details of the visa extensions. Yes. Expl

ain that to the authorities there. And you yourself, since you're so close with them, you oversee Jewcom's activities. That also will be the perfect way for us to be kept informed, unofficially of course, of everything that is going on there."

Matsuoka was pleased with his solution. Kotsuji was ecstatic. He went straight from Tokyo to Kobe, not even stopping off at Kamakura, and got in touch with the municipal officials in charge of transit visas.

Kotsuji's subsequent local negotiations were typically Japanese in indirectness. On two evenings, separated by a few days for recuperation, he entertained local officials lavishly. He had borrowed three hundred yen (about one hundred and fifty dollars), from his brother-in-law to provide gargantuan feasts, complete with samisen players, geishas and endless sake, at Kobe's best restaurant. But aside from a brief mention of the fact that he was concerned for the plight of the refugees and a quiet allusion to his friendship with Matsuoka, absolutely nothing was said about extending visas. Not until the third party did Kotsuji casually bring up the problem of the visas. The official in charge nodded his understanding. He also, he said, had been concerned about this problem. Could they, perhaps, work something out?

Within a few days, extension forms had been turned over to Kobe Jewcom. Any refugee in need of a fifteen-day extension filled out the form at Jewcom, and from there it was forwarded to the local government office for validation. From then on, Kotsuji was a gratefully-welcomed member of Jewcom, kept up-to-date on the details of everything that the Jews - refugees and residents alike were doing.

On par with the problem of extending the visas was the question of finding accommodation for the refugees. The first few arrivals had been welcomed into the homes of the community members themselves, but before long the refugees began, literally, to pile up. By mid-July, a broader solution had been devised: Jewcom went into the real estate business. The Housing Committee rented a number of small buildings in its neighborhood, rearranged them dormitory-style and provided them, free, to the refugees. After all they had been through, the refugees were only slightly surprised to find themselves sleeping Japanese style between the soft tatami straw floor and a warm, fluffy, bright-colored futon quilt. The heime, as the dormitories were called in Yiddish, might have been communal, but, under the supervision of the Ladies Committee they were clean, secure and well managed. There were few complaints, even from those who ultimately lived there for seven or eight months.

Physical support - housing in the heime and a cash allotment of one-and-a-half yen (seventy-five cents) per person per day for food - was the most straightforward of the continuing challenges confronting Jewcom and the refugees. By transferring money through American banks to Jewcom Kobe, the Joint Distribution Committee paid the bills; and once the system was set up, administering it was merely a matter of bookkeeping. Serious illnesses were also less of a problem than anticipated.

Japanese doctors were more than generous in giving time, skill and medication, charging either minimal fees or waiving them entirely. (In fact, Kobe's entire Japanese population tended to respond to the refugees with one sympathetic word: kawaiso, "poor unfortunates.") But for Jewcom and the refugees, there was an endless stream of other difficulties. Relatives had to be tracked down in destination countries, usually on the basis of nothing more than a name and partial address, like "Samuel Cohen, Brooklyn." Money had to be found for the trans-Pacific passage. Wherever possible, money would be borrowed from relatives - often very distant family members. Otherwise, funds might come through one of the many religious or communal organizations to which a refugee might belong.

Jewcom also had to provide for the Orthodox religious practices of many refugees. Kosher wine and matzah had to be imported from the United States for Passover. Schedules had to be made to avoid travel on Saturday, a normal working day in prewar Japan. (One group of arrivals did, indeed, spend the Sabbath on the Tsuruga dock. Arriving after sundown on Friday, its leader agreed to disembark - lest they all be taken back to Russia - but refused to go further till after sundown on Saturday.) Whenever chicken could be afforded, arrangements had to be made for kosher slaughtering. Most important, Jewcom continually had to be the intermediary between the very Oriental minds of the Japanese bureaucrats and the very Jewish presumptions and methods of the refugees. And sometimes, it seemed that nothing short of a miracle was needed to rescue a group of refugees from a particular catastrophe.

Early in 1941, a ship landed at Tsuruga counting among its passengers seventy-two Jews who had no destination visas whatsoever, not even the Curacao stamp. These seventy-two people were not frightened children, like Moishe Katznelson, who had lost their visas. They were adults to whom Consul Sugihara had issued Japanese transit visas which were conditional upon their getting some sort of destination visa. This, these particular refugees had not been able to do. Sadly, but implacably, Japanese immigration officials refused to let them into the country.

The ensuing dockside scene was not unlike those already being played over and over at concentration camps throughout Europe. Amid screaming and wailing, some passengers were allowed to turn toward the life, the hope, the future that Japan offered; others were forced away, compelled to remain on a ship that would only take them back to Russia and certain doom. Frantically, Kobe Jewcom contacted Japanese authorities in Kobe, Yokohama and Tokyo. They could do nothing. Cables were sent to government offices in Washington, New York, London, all over the world: Please save these people! No help came. Inexorably, the departure time came, and the ship, with its seventy-two desperate, desolate passengers, began steaming back toward Vladivostok.

Kobe Jewcom was not a place where secrets were well kept. One of those who heard of the plight of the seventy-two refugees was Nathan Gutwirth, the same shy young man who had first approached the Dutch ambassador in Riga. Again, he sought the help of his government, this time going to the home of the Dutch consul, N.A.G.de Voogd, in Kobe. De Voogd immediately asked the shipping line to radio its captain instructions not to offload the passengers at Vladivostok if, at any time before reaching the Russian port, he received another cable that visas were waiting for them in Japan. Then the Dutch consul began stamping out an official declaration that "No visa to Curacao is required" in the name of each of the seventy-two refugees. The second cable reached the captain just as the coast of Russia appeared on the horizon: Seventy-two properly typed, stamped and endorsed visas had now been approved by the Japanese immigration officials. The refugees were safe. Cruelly, however, the captain kept this news from the passengers.

For their part, the terrified Jews had already decided that not only would they refuse to leave the ship voluntarily in Russia, they would not even appear to be on board. As the ship cruised into Vladivostok's Golden Horn Harbor, seventy-two bodies lay motionless as corpses, flat on the floor in the ship's hold. Minutes passed, then hours. The terrified refugees could not comprehend why they had not been roused at bayonet point and harried off to a Russian police station. Finally the ship's engines began rumbling to life, and one of the men could no longer stand not knowing. Cautiously, he peered out of the hold, only to find the captain grinning down at him.

"We are going back to Japan," the officer announced cheerfully. "You do have visas for Curacao after all!"

As a joke, it was sick - but the refugees were too jubilant over their reprieve to care. In Kobe, meanwhile, Consul de Voogd dropped off a stack of signed and stamped Curacao visa forms at Jewcom headquarters. Never again would that particular catastrophe loom so near.

Kobe Jewcom solved the problems as they arose - and those that could not be satisfactorily solved, they made the best of, always with patience and compassion. But there was one problem that remained insoluble. As 1941 progressed, it became unmistakably obvious that fewer refugees were leaving Japan than were coming in. The doors of the world, which had never been opened very wide for them, were closing even further. Immigration visas, acquired in good faith, suddenly were no longer valid. Guarantees evaporated; documents were declare

d insufficient or unacceptable. Already, by the end of January, there were two hundred and seventy refugees held over in Kobe. Where these, and subsequent arrivals holding the worthless Curacao visa stamp would go, was absolutely unknown. Avram Chesno sat on a concrete bench in one of Kobe's small hillside municipal parks and stared out over the scene below. It was a typical winter day - cold, dry, the air brilliant with sunshine. Camelia bushes along the park paths were budding; a few of the Japanese plum trees had already broken out in spherical splotches of red and white. Just down the hill in a schoolyard, uniformed elementary school boys were engaged in their compulsory daily military exercises, marching around with stick-guns held stiffly against their shoulders. And far below, over the rippling red and blue tile roofs of the tiny hillside houses, past the open cut of the busy railroad right-of-way, and through the plain gray cement blocks that were the waterside office buildings, there was the harbor. Dotted with ships, civilian and military, of every conceivable shape and size, the water was sparkling blue. It was a beautiful day, the kind that would make anyone glad he was alive just to see it. But the brighter the sun shone, the more depressed Avram became.

The night before, he had heard a translation of the latest news of Warsaw. Food rations for Jews, already barely sufficient to keep one alive, had been cut in half. There was no meat, except horsemeat, anyway. The average daily ration now provided scarcely a thousand calories against the bitter winter cold and the constant physical struggle merely to stay alive. There was so little coal that it was being called "black pearls." And over the past two months, the Germans had systematically confiscated every fur coat, fur lining, even fur collar and cuff in the ghetto.

After the broadcast, he couldn't sleep. Lying under a warm futon, the aftertaste of his dinner still apparent, Chesno had felt repelled from his past as if pushed away by the force of a reversed magnet. Europe was no longer a place to return to, not even in one's imagination. They had destroyed his Europe. They had taken a rich, full world of joy and possibility and life, and were savagely battering it into an agonizing, unrelieved day-and-night struggle simply to exist. Their bombs had made rubble of the buildings and their sadistic decrees were grinding out the life of the people. His early life his education, even the culturally Jewish atmosphere he had grown up in - had created in him a passion for living. Hadn't the simple toast, 1'chaim (to life), been the crowning moment at every occasion? But with his ears still hearing the statistics of suffering, his mind projecting the images of starvation and pain that constituted "life" for those who had not escaped, Avram could not help but feel that he was glad his Ruthie was already safely out of it.

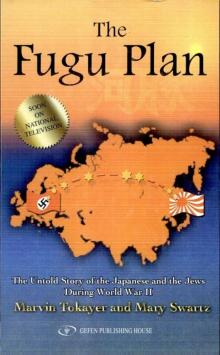

The Fugu Plan

The Fugu Plan